What We Know About ASMs & Risk of Major Congenital Malformations and Adverse Neurodevelopmental Outcomes

Studies examining the effects of anti-seizure medications (ASMs) on children exposed during pregnancy have primarily focused on two key outcomes:

- Fetal malformations

- Adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes

Most research has found that the risks associated with exposure to ASMs are relatively low compared to exposure to other substances like thalidomide or fetal alcohol exposure.

However, some ASMs carry a higher risk than others. Clinicians need to consider these variations and weigh the potential risks and benefits of different ASMs when treating pregnant patients with epilepsy.

Limited or no data on major congenital malformations or neurodevelopment

| Brivaracetam Cenobamate Clobazam Clonazepam Diazepam | Eslicarbazepine Ethosuximide Epidiolex Fenfluramine Gabapentin | Lacosamide Lorazepam Perampanel Pregablin Rufinamide Vigabatrin |

Visit the American Academy of Neurology's Practice Guidelines for additional information.

Topics covered on this page include:

Neurodevelopmental Outcomes For Children Born To Parents Taking ASMs

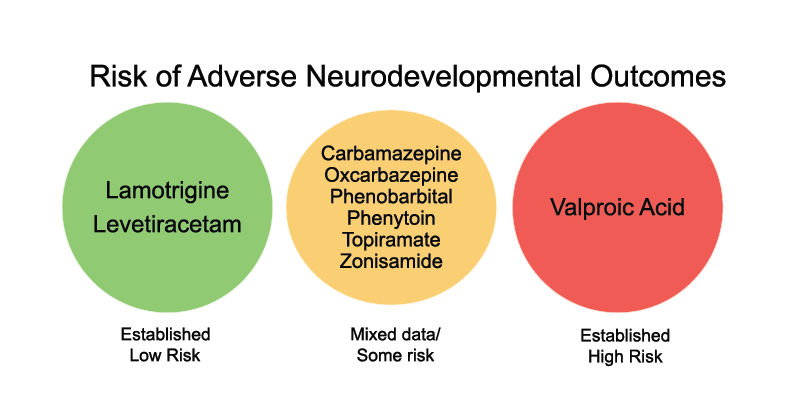

Several studies have followed children exposed to ASMs during pregnancy and assessed neurodevelopmental outcomes. These studies also found that:

- Data on valproic acid suggests highly elevated risk:

- Valproic acid exposure has the highest risk of exposed children having lower global IQ and verbal IQ when compared to other ASMs

- Valproic acid associated with increased risk of autistic spectrum disorder when compared to other ASMs

- Lamotrigine exposure appears to carry a relatively low risk of adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes.

- Levetiracetam also carries a low risk, based on more limited data.

- The data on carbamazepine are mixed but generally suggest a low risk.

- The data on topiramate are more mixed and suggest no clear effect on neurodevelopmental outcomes.

- The data on valproic acid suggests highly elevated risk.

Valproic acid exposure during pregnancy was found to be associated with adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes (cognitive and behavioral) in children when compared to children born to mothers without epilepsy and children born to mothers taking other anti-seizure medications. Specifically, children exposed to valproic acid during pregnancy may exhibit lower global IQ, lower verbal abilities, and have an increased risk of autism and autism spectrum disorder. Moreover, these neurodevelopmental effects continue into the school-age years.

We have limited data on the other seizure medications, and more research is needed to understand their effects on the neurodevelopment of children born to patients who take these medications during pregnancy.

ASMs & Major Congenital Malformations

Major congenital malformations (MCMs) are fetal abnormalities that impact daily health and function or require surgery. In the general population, pregnancies carry a background risk of 2-3% for MCMs. Examples include:

- Spina bifida

- Heart defects

- Cleft lip/palate

- Urogenital defects

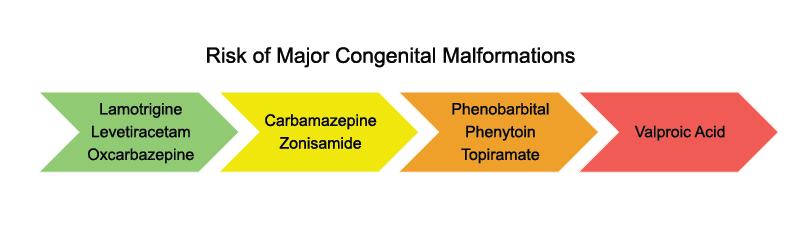

Pregnancy registries have provided valuable insights into the risk of MCMs associated with ASMs by following patients from their early pregnancy stages. Among all ASMs:

- Lamotrigine (3.1%), levetiracetam (3.5%), and oxcarbazepine (3.1%) have the lowest prevalence of malformations based on data from these pregnancy registries and meta analysis. Prevalence of MCMs were within the range for children who were not exposed to any ASM during pregnancy (2.4-2.9%).

- Valproic acid has the highest prevalence of malformations (9.7%) and neural tube defects (1.4%).

- Phenobarbital has the highest prevalence of child having a heart defect (4.4%)

- Phenobarbital (2.2%) and topiramate (1.2%) exposure results in increased prevalence of oral clefts

- Valproic acid has the highest prevalence of urogenital (1.2%) and renal (1.4%) malformations. Research suggests that carbamazepine is generally low-risk.

Visit the American Academy of Neurology's Practice Guidelines for additional information.

Importantly, the risk of MCMs appears to correlate with the valproic acid dose and level of the medication. For example, a patient taking valproic acid at the dose of:

- <700 mg a day has a 5.6% risk of MCMs

- 700 - 1500 mg/day has a 10.4% risk of MCMs

- >1500 mg/day has 24.2% risk of MCMs.

It is essential to recognize that even low-dose valproic acid presents some risk, along with potential risks of neurodevelopmental effects, as you can see in the above chart. Clinicians should be aware of these varying risks when treating pregnant individuals with epilepsy to optimize the health of the patient and their baby.

Impact of ASMs on Fetal Growth

Certain ASMs can impact fetal growth differently.

- Topiramate exposure during pregnancy has been linked to a risk of infants being born small for their gestational age (SGA).

- Fetal exposure to topiramate is also associated with infants born with low birth weight, which carries greater long-term health risks.

Fetal growth monitoring can help identify any potential problems early on and is recommended for pregnant patients with epilepsy, especially those on these medications. Visit the pregnancy management page to see when this monitoring is recommended during pregnancy.

ASM Polytherapy

There is no definitive increased risk of polytherapy compared to monotherapy in pregnancy. There is, however, limited study. In some patients, combining safer medications can be a good strategy. For example, a baby exposed to the combination of levetiracetam and lamotrigine in pregnancy is at lower risk for malformations and adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes than a baby exposed to valproic acid.

ASM Generic vs Brand Names

| ASM Generic Name | ASM Brand Name |

|---|---|

| Brivaracetam | Briviact® |

| Cannabidiol oral solution | Epidiolex® |

| Carbamazepine | Carbatrol®, Tegretol® |

| Cenobamate | Xcopri® |

| Clobazam | Onfi®, Sympazan® |

| Clonazepam | Klonopin® |

| Diazepam | Valium® |

| Diazepam (Nasal spray) | Valtoco® |

| Diazepam (Rectal gel) | Diastat® |

| Eslicarbazepine | Aptiom® |

| Ethosuximide | Zarontin® |

| Everolimus | Afinitor® |

| Felbamate | Felbatol® |

| Fenfluramine | Fintepla® |

| Gabapentin | Neurontin® |

| Ganaxolone | Ztalmy® |

| Lacosamide | Vimpat® |

| Lamotrigine | Lamictal® |

| Levetiracetam | Keppra® |

| Lorazepam | Ativan® |

| Midazolam | Xanax® |

| Midazolam (Nasal spray) | Nayzilam® |

| Oxcarbazepine | Trileptal®, Oxtellar® |

| Perampanel | Fycompa® |

| Phenobarbital | Luminal® |

| Phenytoin | Dilantin®, Phenytek® |

| Pregabalin | Lyrica® |

| Primidone | Mysoline® |

| Rufinamide | Banzel® |

| Stiripentol | Diacomit® |

| Tiagabine | Gabitril® |

| Topiramate | Topamax®, Trokendi®, Qudexy® |

| Valproic Acid, Valproate, Divalproex | Depakote® |

| Vigabatrin | Sabril® |

| Zonisamide | Zonegran® |

Guide Your Patients

There are ASMs with a low risk of fetal malformations or adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes. These ASMs also present little risk to babies if women take them while breastfeeding. It is important to be very clear with patients about the existing research, what it shows, and what we don’t yet know.

Patients considering pregnancy should be advised of the potential risks of certain ASMs on child development. However, patients should be reassured that there are options with little or no elevated risk to the fetus. Emphasize that they should not stop taking medication due to fear or perceived risk, as abrupt discontinuation can be harmful. Instead, a collaborative approach should be taken to assess the benefits and risks of ASMs for both the patient and the developing fetus. Ensure your patients with epilepsy are aware that a healthy pregnancy is achievable with some preparatory planning.

Reviewed by: EPMC Expert Panel, March 2025